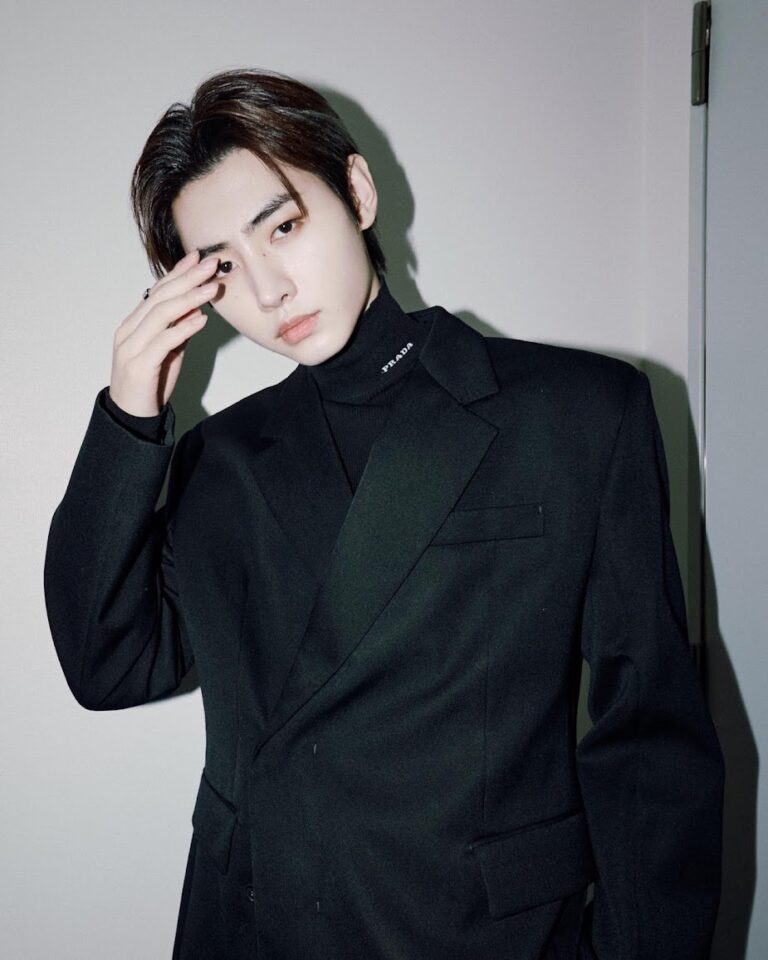

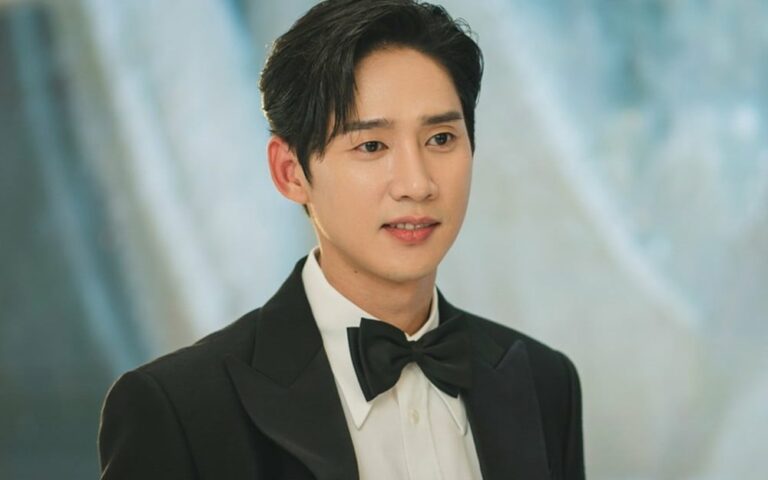

Kim Soo Hyun: Navigating the Waters of Stardom and Romance

Kim Soo Hyun, one of South Korea’s most beloved actors, has recently found himself at the center of a media whirlwind due to rumors regarding his personal life. As a star who has consistently captivated audiences with his performances, his dating life has become a subject of intense speculation and interest among fans and media…